In 2019, about 1 out of every 8 Georgians (over 1.3M) were living in poverty.

Georgia is in the top 10 states with the worst urban air quality.

Of the 23 designated EPA Superfund sites in Georgia, only one is located in the Atlanta metro area.

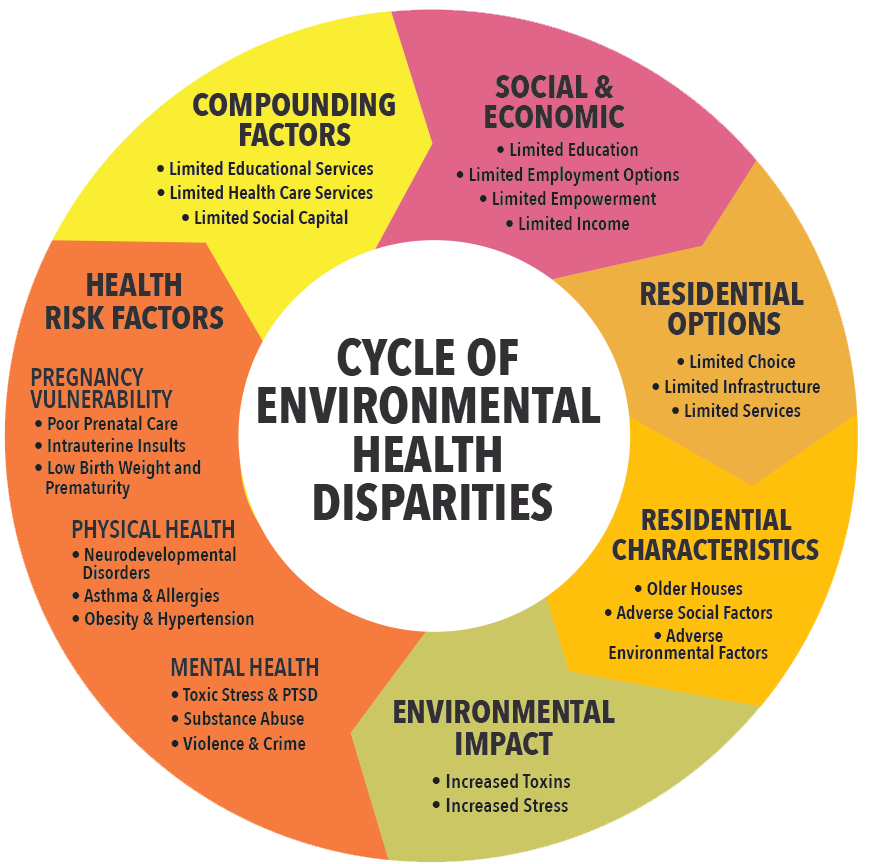

Unfortunately, the effects are not equal. Low-income individuals are more likely to live in polluted areas with less green space. And chronic health conditions are more prevalent in those residing in environmentally-poor living conditions.

Thus, poverty, the environment, and health are linked. And those living in poverty can become trapped in a vicious cycle. For example: bad air quality is correlated with increased chronic illnesses; being out sick leads to poor performance in work or school; poor performance leads to an inability to get ahead; this leads to living in unhealthy environments; and the cycle continues.

Rural Environmental Health

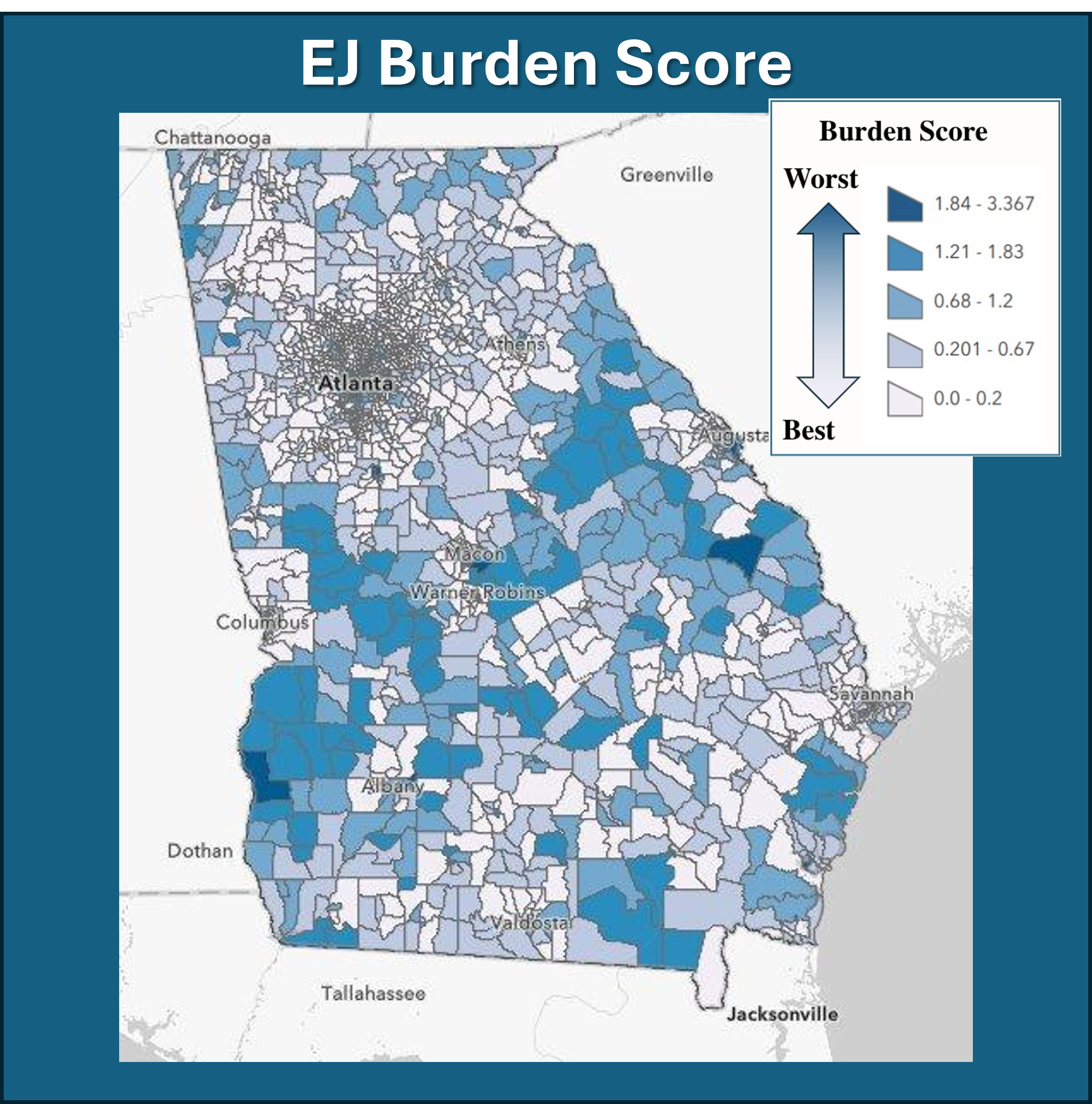

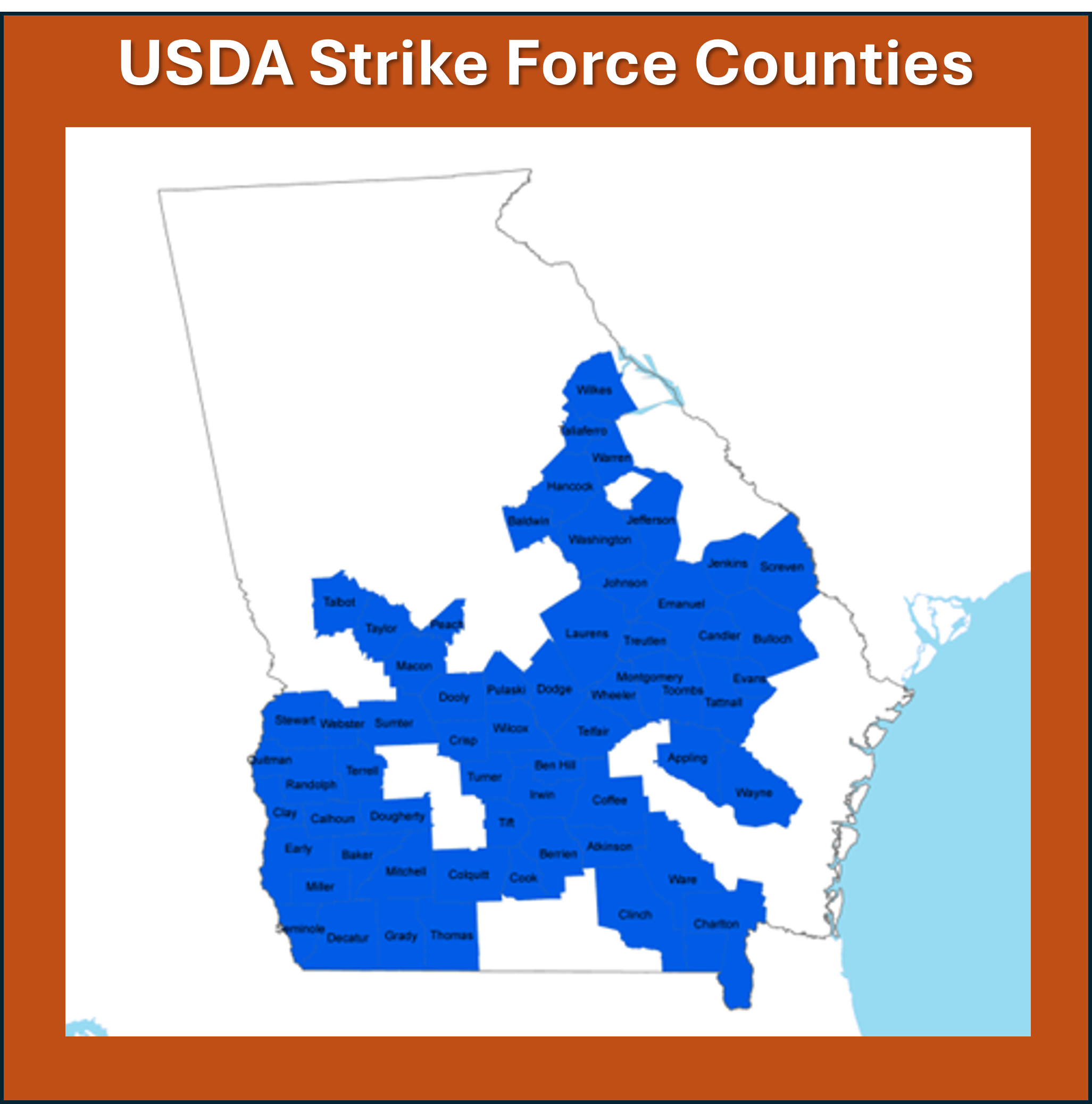

Georgia’s rural areas oftentimes collectively bear a much higher environmental burden than their urban counterparts. While economic development promises jobs to often-depressed areas, there are often fewer and lower-quality jobs available than communities hope for. Additionally, these projects typically do not consider input from the local community that stands to gain or lose from the impacts of the development.

Rural communities in Georgia are especially vulnerable to environmental injustice. Of the 23 designated EPA Superfund sites in Georgia, which are sites that are federally designated as a hazard and require extensive cleanup from pollution and other environmental damage, only one is located in the Atlanta metro area.

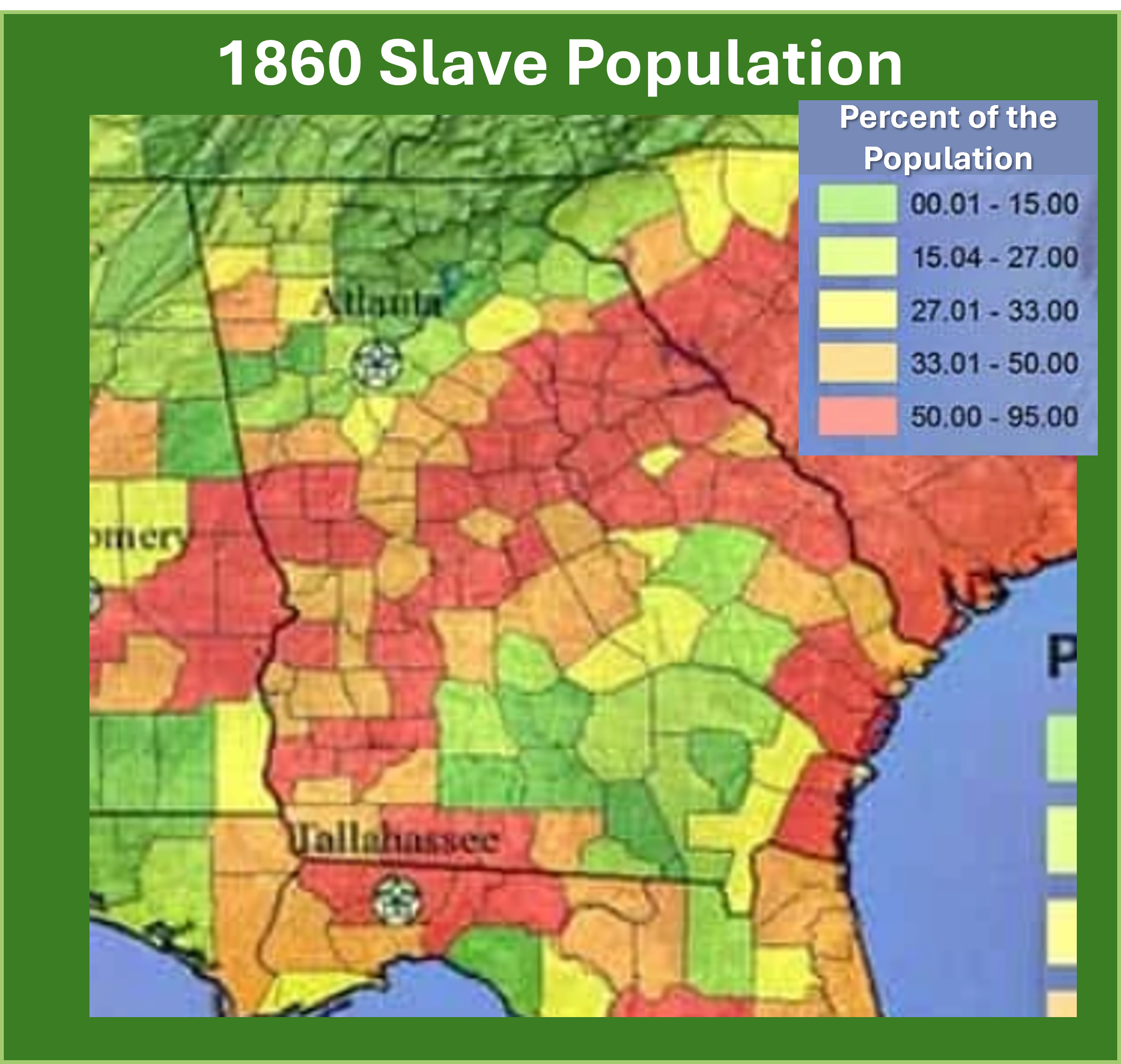

The three images below show that a given community’s relative environmental burden correlates heavily with rural poverty and historical populations of enslaved people. Many of Georgia’s most rural counties are designated “StrikeForce” counties, where 30% of the population has lived 30% below the federal poverty line for at least 30 years. These counties also have higher-than-average proportions of African Americans than the rest of the United States, owing in large part to the historical distribution of enslaved people and the resulting “Black Belt.” These areas are targets of new economic development, yet they are also highly burdened.

Specific Rural Issues

Processing crypto transactions and finding new digital coins takes a lot of energy. Crypto data centers are beginning to pop up around Georgia, but they bring very little if any economic development to local communities.

Protecting Communities from Crypto Mining Excess – Science for Georgia

Touted as a sustainable fuel option with the potential to bring jobs, wood pellet plants can also bring air and noise pollution to communities. Policymakers must decide if the potential for job growth is worth the public health risk the local community would face.

We have the technology to take carbon dioxide out of the air, but we have to bury it somewhere. Carbon burials typically happen deep underground, but the process is energy-intensive and carries risks to rural communities and geologic formations. Might it be buried in Georgia, and if so, where?

Some Georgians rely on household water wells for drinking water, and they badly need to be replaced. Meanwhile, new industrial developments threaten to drain the Floridan aquifer. To balance drinking water needs and economic growth, Georgia need should minimize water usage as much as possible while drawing on “gray water” sources instead of the Floridan aquifer for industrial uses. Georgia currently allows gray water usage for toilet flushing and subsurface irrigation but expanding its usage could save millions of gallons in water.

The growth of solar as a renewable energy option creates a new demand for land to host solar panels in rural areas. Although these interests may appear to work against one another, the solar and agricultural industries can actually work in tandem to serve rural communities and the rest of the state.

Environmental Health

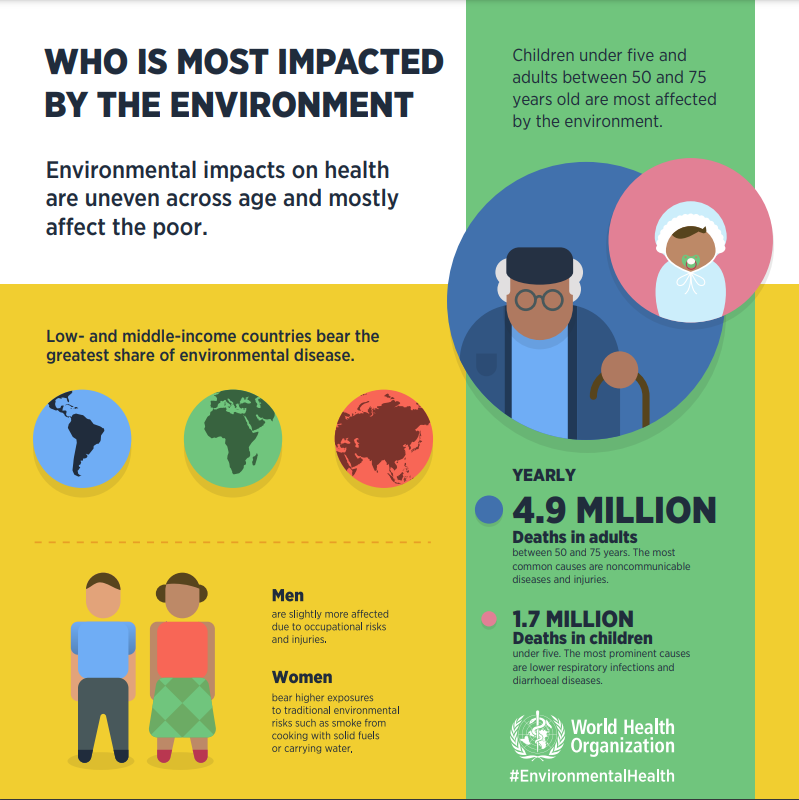

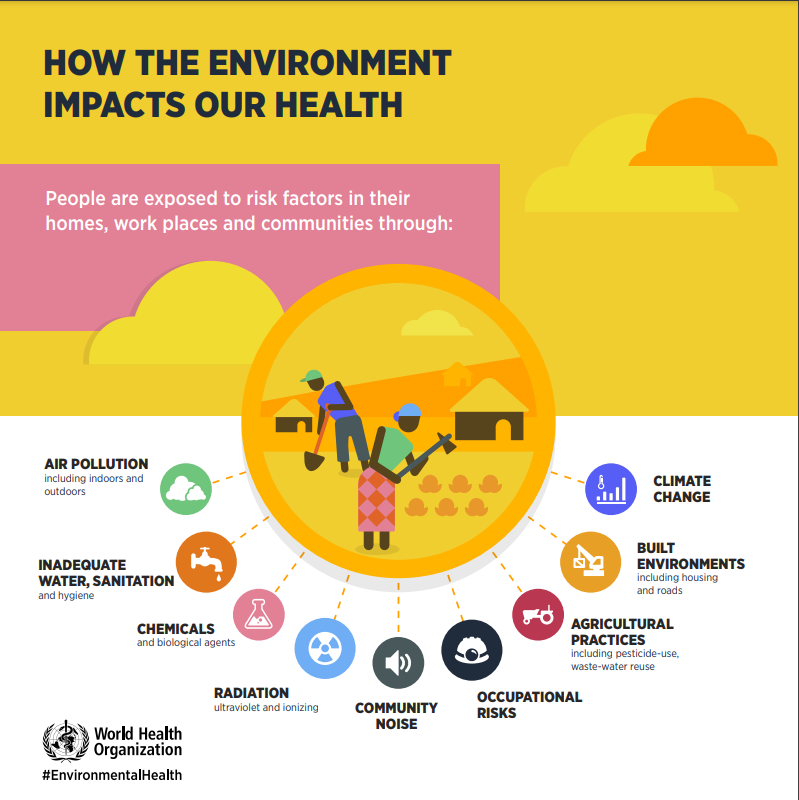

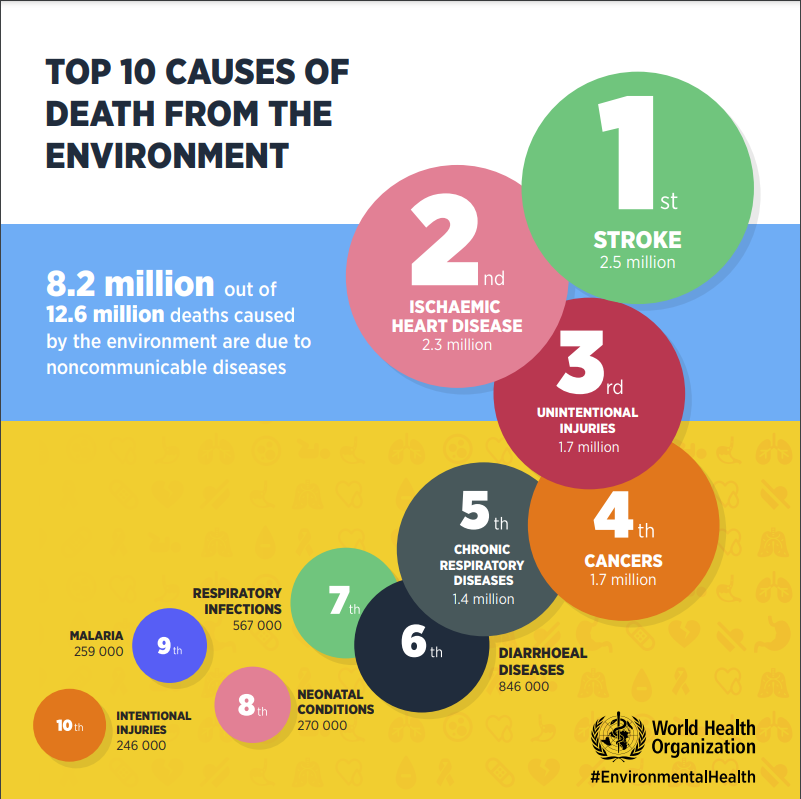

From where you live, work, and exercise, to what you breathe, eat, and drink, the environment is constantly shaping our health.

This interconnectedness is studied via a broad scientific area referred to as environmental health, which focuses on the relationship between human health and the environment.

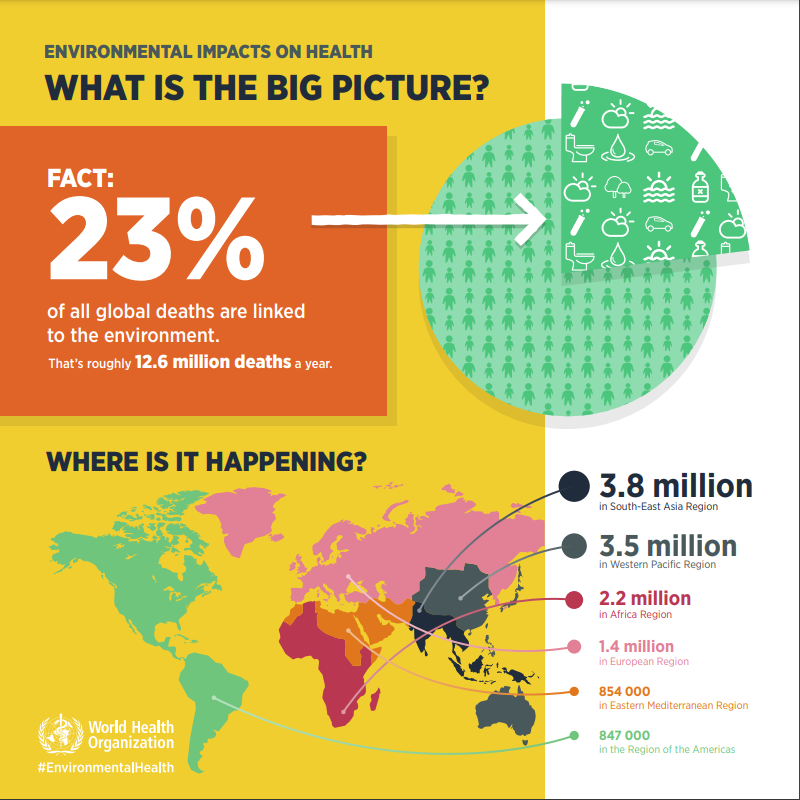

The World Health Organization made the infographics shown here to show the impact of the environment on the global population.

Solutions and Mitigations

The good news is that cycles can be transformed from vicious to virtuous through external, disruptive, change. And every positive step we take can creative positive impacts.

Individual Actions All of Us Can Take

Cut down your single use plastics. Recycling them is harder than you think.

Cut down on food waste and compost the inevitable by products.

Lean how to have a larger impact on composting in your neighborhood.

Advocate for change

Community Benefit Plans

Although Community Benefit Plans have been around for decades, the federal government recently took an important step toward enshrining them. For nearly all projects with funding from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law or the Inflation Reduction Act, the Department of Energy (DOE) requires a Community Benefit Plan. This plan requires developers and industrialists to consider community engagement, quality jobs, diversity, equity, and inclusion, and Justice40, which seeks to direct federal climate investment to historically disadvantaged communities. These plans must be specific and actionable and becomes a contractual obligation for the funding recipient.

Community Benefit Plans are a key way to keep developers accountable for the external impact their plans have. Many plans often promise jobs but never deliver, and most fail to account for environmental externalities. By enshrining community benefits in a contract, CBPs can be vital for upholding environmental justice in rural communities. While most CBPs under the Inflation Reduction Act are in their infancy, the effects could be widespread. What remains to be seen is how they get implemented.