by Brooke Lappe

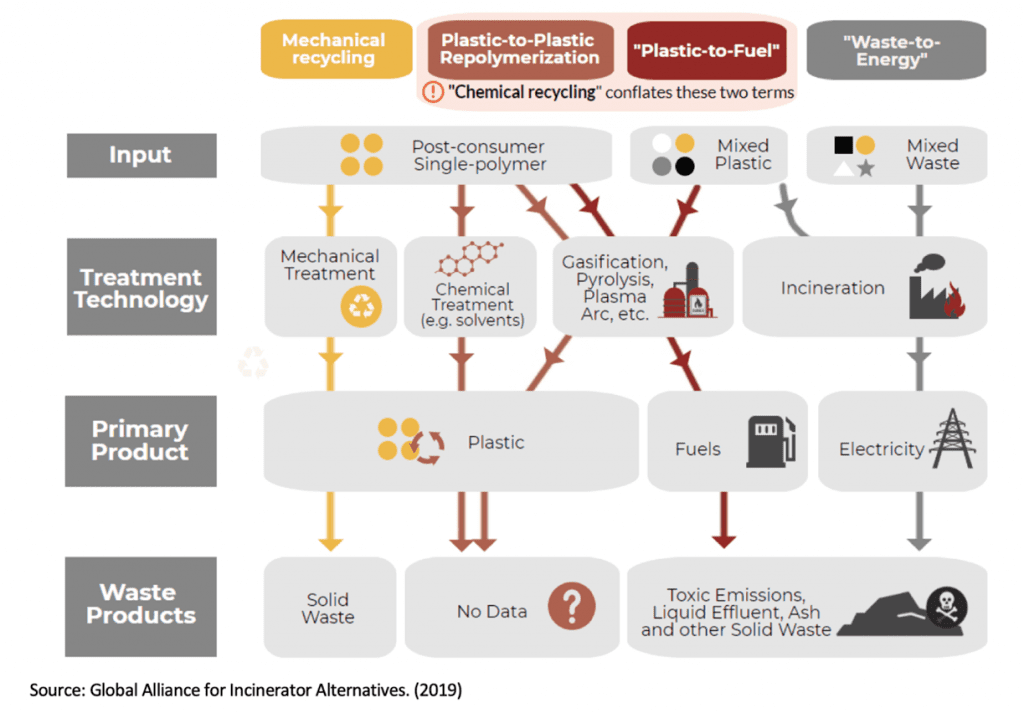

In June, Brightmark, a global waste solutions company, announced it would be spending $680 million to build the nation’s largest chemical recycling facility for plastics in Macon, Georgia. This plant would turn plastic into fuel through pyrolysis, otherwise known as plastic-to-fuel technology (PTF). The announcement has been followed by support from local government but skepticism from environmental groups concerned that this could be yet another fossil fuel industry green washing scheme.

Chemical recycling is a newly operational process that has seen an influx of funding since 2017, after China enacted the National Sword Policy that prevented the U.S. from exporting their plastic waste to China for recycling. This has created a gap in the U.S. for plastic disposal, leaving legislators scrambling to find more economically feasible plastic solutions than mechanical recycling, which oftentimes is not economically feasible because of high costs and limitations for certain types of plastic. Many local recycling plants have shut down in recent years because of this reason.

Praised in some academic circles as the solution to the plastic problem, chemical recycling has won over many because of its lower costs and ability to break down nearly all types of plastic. However, most research of chemical recycling is conducted in laboratory settings, lacking the operational and environmental scope needed to evaluate it as a feasible plastic solution. There has been little research on chemical recycling from an environmental standpoint; however, a recent review of scientific and technological evidence shows that the chemical recycling industry is overrun with environmental, technical, and economic problems. The choice of Macon-Bibb County, with a large historically marginalized population, is concerning from an environmental justice standpoint.

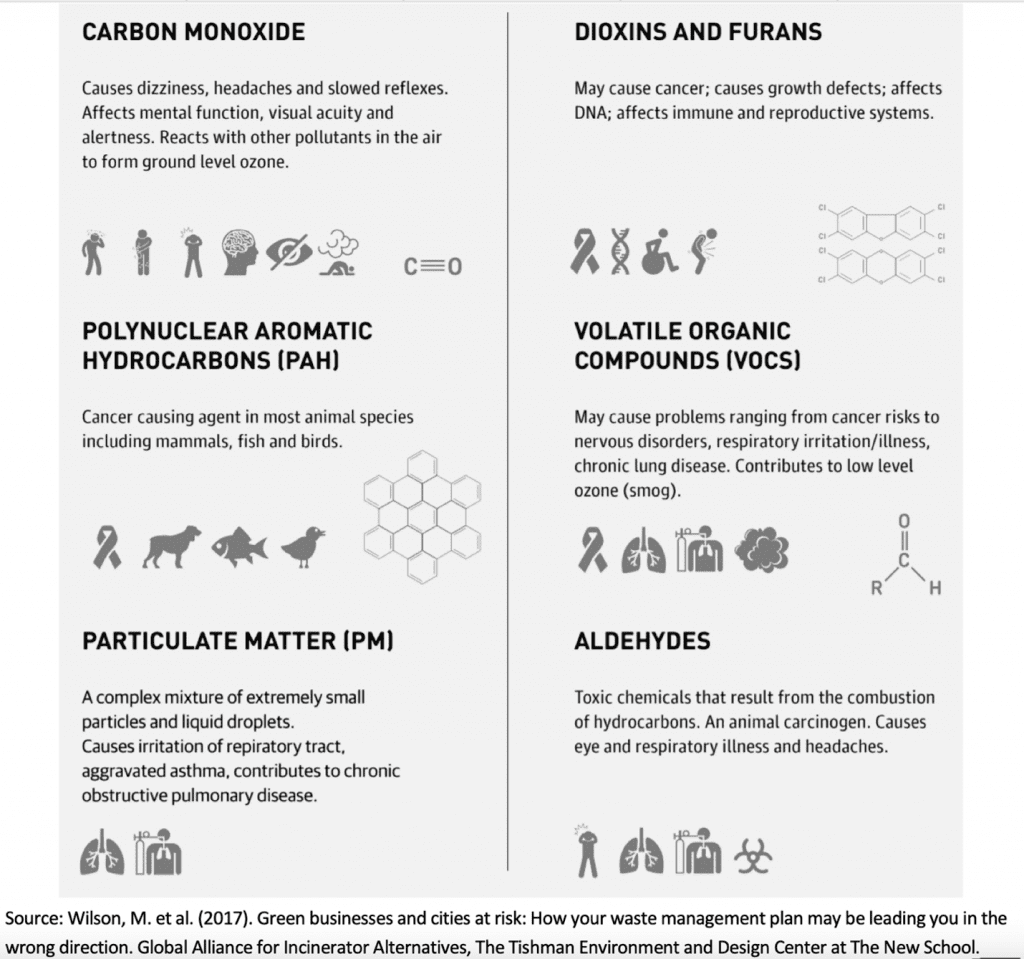

Toxic chemicals are released into the environment through several chemical recycling pathways. The toxic chemicals that already exist in plastic, and are known to harm human health, are released, risking exposure to workers, communities near facilities, and the environment. These chemicals include bisphenol A, phthalates, benzene, brominated compounds, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs). New toxic chemicals can also be created during the chemical recycling process. Brightmark has yet to publish the toxicity tests of their fuels and products from their PTF plant in Indiana. The toxic waste produced from chemical recycling plants threatens communities living near dump sites, incinerators, and cement kilns, who are inevitably affected by proximity even if toxic waste is disposed of properly. Brightmark has already applied for a permit from the state Environmental Protection Division to release emissions such as carbon monoxide, nitrous oxide, VOCs, and other pollutants, in a move that foreshadows the increased pollution soon to come in Georgia.

Chemical recycling has an environmental cost that may outweigh any potential benefits: its carbon footprint. This is especially important for the Brightmark plant, which will use plastic to fuel (PTF) technology. Beyond perpetuating the climate crisis by preventing a transition from fossil fuels, the PTF process uses considerable energy, which is also supplied by burning fossil fuels, ultimately releasing additional greenhouse gases. Instead of conserving material in a circular process, plastic-derived fuel adds to the carbon footprint of the plastic lifecycle and creates further virgin plastic production to replace the plastic lost as fuel. Incineration is the primary source of greenhouse gas emissions, and over 850 million metric tons of greenhouse gases were released from this process in 2019 alone. This is approximately equal to the emissions of 189 coal power plants, close to the total number of coal plants in the U.S.

Even if the resulting toxic chemicals and carbon footprint was worth the additional fuel production, research has not even shown the chemical recycling process is operationally feasible at scale. Of the 37 chemical recycling facilities proposed since the early 2000s, only 3 are currently operational, and none of them are known to have successfully recovered plastic or created new plastic. Note that one of these existing plants are owned by Brightmark. Chemical recycling plants require costly investments for infrastructure and market development, and PTF operations are fragile because of their dependence on unstable oil and gas markets. The shutdown of Agilyx’s Tigrad chemical recycling plant in 2016 because of an oil price drop is a prime example of the economic vulnerability of these plants. Dropping oil and gas prices have reflected the systematic weakness of the fossil fuel industry, and these low prices will keep the production of new plastic cheap, which damages the market value and feasibility of plastic recycling because it is cheaper to buy fuel than make plastic-derived fuel. The support of chemical recycling by petrochemical companies such as Dow and Shell, despite of the lack of evidence as to technological and economic viability, clearly shows how desperate they are to hold on to fossil fuels in the era of decarbonization. Additionally, the tendency of polluters to rely on new greenwashed technological “fixes” has also increased, as companies that rely heavily on plastic bottles (beverages, consumer products) partnering with chemical recycling companies, instead of taking responsibility for their plastic waste that threatens the planet and human health.

Recent legislation made it easier for Brightmark and other gasification and pyrolysis facilities to operate in Georgia. In 2018, HB 785 passed, which reclassifies post-use plastics as raw materials for “manufacturing” and regulates gasification/pyrolysis facilities as manufacturing facilities instead of waste management facilities, which have different environmental standards.

Chemical recycling is an environmental health risk and the choice of Macon-Bibb county, with 55% Black residents, as the site of the new plant continues the tradition of placing polluting infrastructure in marginalized communities. The county had a history of poor air quality, with the American Lung Association “State of the Air” report grading Macon-Bibb County a C in 2017, as a result of their ozone levels.

Environmental justice, and the history of injustice in Black, Latinex, and Indigenous communities, has shown us the industry has typically has a “build and sell first, protect health later” approach. It seems that this Brightmark plant will be taking the same approach, with little community involvement in the planning and placement of the plant. Public involvement in decisions and regulatory oversight along the entire chain of the industry is necessary to protect communities, workers, and the environment. For historically marginalized communities it is especially important to prevent further harm to overburdened communities. This is where newly introduced environmental justice legislation in Georgia, HB 339 and HB 431, are essential. HB 339 creates a commission to conduct scientific analysis and prepare a report to include facilities regulated by the Georgia Environmental Protection Division (EPD) to determine disproportionate environmental impacts on people of color and low-income communities. HB 431 will establish additional permit application requirements for new or expanded facilities in overburdened communities (low income, minority, limited English proficiency), including the preparation of an environmental justice impact statement, issuance of the environmental justice impact statement to the department and to the local government in which the community is located, and public hearings in the overburdened community. If these bills were law, Brightmark would have to evaluate their environmental impact to ensure they are not further burdening Macon-Bibb County.

As the public pushes industry to move away from fossil fuels and plastic, the future of the plastic-to-fuel industry is at best questionable and at most a distraction from addressing the root cause of the world’s plastic waste crisis. The plastic chemical recycling industry has struggled with decades of technological difficulties and poses an unnecessary risk to the environment and health, and a financially risky future that is incompatible with a climate safe future and circular economy. Far more mature and viable solutions are to be found upstream in plastic tax/ban policies, such as Georgia SB 104, which focuses on reducing the production and consumption of plastic.

We encourage you to learn more about chemical recycling and contact your legislator to ensure that the Brightmark plant undergoes appropriate health and environmental scrutiny. The premise of bills HB 339 and HB 431 should be applied to this plant, despite the fact that they are not yet law.

Learn More & Sources

www.no-burn.org/chemical-recycling-us

www.ciel.org/plasticandclimate

https://bellona.org/publication/brief-counting-carbon-a-lifecycle-assesment-guide-for-plastic-fuels

https://comingcleaninc.org/resources/whos-in-danger-report

https://www.ciel.org/reports/pandemic-crisis-systemic-decline

https://theintercept.com/2019/07/20/plastics-industry-plastic-recycling

https://cen.acs.org/environment/recycling/Plastic-problem-chemical-recycling-solution/97/i39