Science for Georgia, Georgia Clinicians for Climate Action, and Environment Georgia have drafted the below letter raising our concerns about the plastics-to-fuel (i.e., plastics incineration) industry’s expansion in Georgia and calling on decision makers to consider these facilities’ negative impacts on our environment and our health as they review proposals for new petrochemical plants in cities like Macon and Augusta.

Please find the letter and signatures below:

Full Letter

In June of 2021, the San Francisco-based company Brightmark announced its intention to build the world’s largest plastic-to-fuel facility in zip code 31216, Macon, Georgia. Brightmark stated that the facility would cover 5.3 million square feet and intake 400,000 to 800,000 tons of plastic trash each year from all over the Southeast region. The facility would burn these plastics at temperatures over 500 °C and condense their vapors into fuels such as diesel.

Brightmark refers to this plastic-to-fuel operation as “chemical recycling,” a term denoting relatively new plastic treatment technologies that use a combination of heat, pressure, and/or chemicals to turn plastics into fuel.Brightmark is only one of many companies pushing these plants around the country.

Plastic-to-fuel may sound like a win-win situation. Unfortunately, it is not. As members of the science, engineering, public health, and medical communities, we have composed this letter to outline (1) why this technology is unproven, (2) the harm it will cause to the environment, and (3) the subsequent harm it will cause to people. We urge policymakers and leaders to carefully weigh the consequences before allowing plans for this plant and others like it to proceed in the state of Georgia.

Plastic-to-fuel methods are unproven. There is a lack of research on the proof of success or failure of plastic-to-fuel in practice due to a lack of real-world operational data, and existing research[i] suggests that it will be a challenge to scale up from a laboratory to an industrial setting. Optimistic projections estimate plastic-to-fuel will not become cost-competitive for another thirty years.[ii] Of the 37 facilities proposed in the United States since the early 2000s, only three are operational today.[iii] For example, althoughBrightmark originally stated that their plant in Ashley, Indiana would start up by “late 2020,”[iv] it still has not started commercial operation as of March 2022.[v] Similarly, the Florida-based company PureCycle has announced plans to build a facility in Augusta, Georgia which it claims will purify polypropylene, a difficult-to-recycle type of plastic. However, the solvent-based purification technologies PureCycle plans to use are still in the pilot phase and cannot process mixed plastic waste,[vi] and the company’s existing facility in Ironton, Ohio is not operational.[vii]

Despite the name “chemical recycling,” plastic-to-fuel conversion is unsustainable and does not offer a solution to our plastic waste problem. Conventional plastic recycling creates new plastics from old, thereby reducing waste and fossil fuel extraction. Although proponents of “chemical recycling” claim these technologies can create new plastic in addition to fuels, there is no proof of that claim, and based on public records as of July 2020, no U.S. facility has ever done so at a commercial scale.[viii] Currently, this industry only downcycles plastic into low-quality fuels, which does not reduce new plastic production, plastic waste, or fossil fuel extraction. Instead, plastic-to-fuel perpetuates the overproduction of non-recyclable plastic by creating new pipelines for plastic waste and by providing the petrochemical industry social license to continue producing plastic under the guise that it will be “recycled.”

Plastic-to-fuel exacerbates climate change. So-called “chemical recycling” is actually more environmentally damaging than traditional mechanical recycling due to its higher energy cost, larger carbon footprint, and increased toxic byproducts.[ix] Based on industry estimates of technology viability, the pursuit of plastic-to-fuel does not offer a pathway towards sustainability,[x] but rather, due to the need to supplement with other petrochemicals, enables further fossil fuel extraction. The plastic-to-fuel conversion process requires energy input at every stage: pretreatment of feeder-waste-plastic, preservation of the controlled environment for plastic burning, and decontamination of resultant fuels. Finally, the carbon embedded in the plastic itself is released into our atmosphere when the final fuel products are consumed.Processing one metric ton of plastic waste in a pyrolysis facility (the specific process Brightmark would use to burn plastics) results in at least three metric tons of carbon dioxide.[xi] Documentation Brightmark submitted to the Environmental Protection Agency [xii] revealed that 70% of the output from the company’s plant in Indiana would be syngas (carbon monoxide and hydrogen), 80% of which would be burned to power the plant itself and the remaining 20% of which would be flared.Meanwhile, the diesel fuel blends advertised as Brightmark’s end product would account for only 20% of the plant’s annual output by mass. Ultimately, more energy would be spent making fuels from plastic than the fuels themselves contain.

In addition, we are gravely concerned that the massive facility proposed in Macon would be a major source of air pollution and harm the health and quality of life of those who live and work in Macon and nearby communities in Georgia.

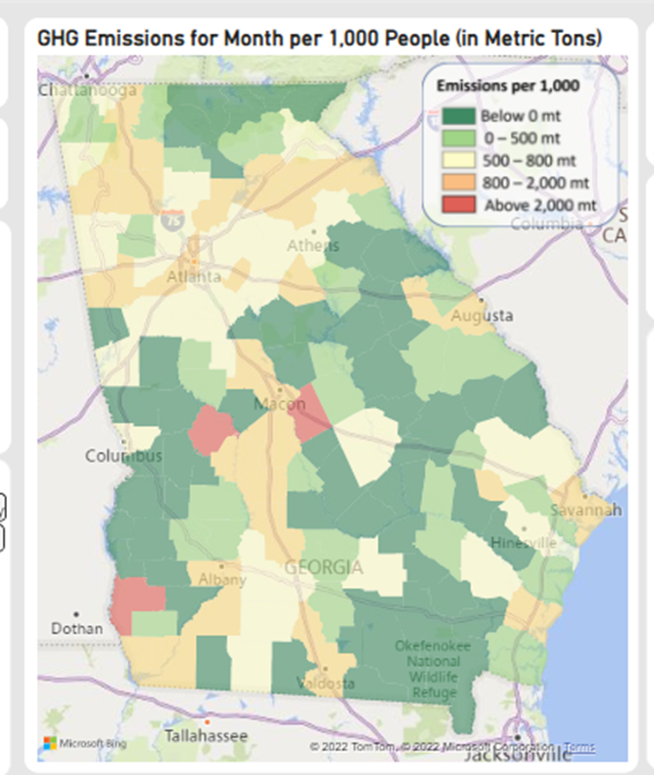

The process used to convert plastic to fuel has the potential to emit large volumes[xiii] of hazardous air pollutants including carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) such as benzene and toluene among other harmful substances. This plant will be located in an area surrounded by homes and schools, all of which will be directly exposed to the emissions, and which are already disproportionately exposed to emissions compared to the rest of Georgia. The workers at the proposed plant will also be particularly exposed. Poor-air-quality environments are bad for health and those living within them were more likely to die of Covid-19.[xiv]

Exposure to any one of these potential hazards can have serious health consequences.[xv] For example, carbon monoxide is a poisonous gas with no smell or taste. It causes headaches, dizziness, confusion, chest pain, and even death. Long-term low-level exposure can cause peripheral artery disease and cardiomyopathy.[xvi] Nitrogen oxides harm the lungs,[xvii] causing inflammation and wheezing. This stunts children’s lung growth, can lead to asthma, and ultimately is the cause of 1.6% of all deaths in the US.[xviii]

The International Agency for Research on Cancer and the World Health Organization[xix] classify benzene as a human carcinogen. Evidence shows it can cause acute myeloid leukemia, acute lymphocytic leukemia, multiple myeloma, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Toluene, in addition to being a known asthma risk factor, can cause nerve damage, cognitive impacts, and liver and kidney disease.

In addition to causing direct harm to health, nitrogen oxides and VOCs are substrates for ozone formation; [xx] any quantity emitted will result in increasing ozone levels. Ozone is also very hazardous to health, [xxi] causing asthma, worsening lung and heart disease, and increasing deaths in exposed populations.

It is a major health concern that the proposed facility is within 3 miles of 8 schools, preschools, and daycares. Moreover, 30 percent of the population in the area is under 18 years of age. These toxins are hazardous to all humans; however, some are more at risk than others, including children, pregnant women, and the elderly. Children, whose brains and bodies are still growing and developing,[xxii] are more vulnerable to the effects of toxic pollutants[xxiii] due to their size and physiology. They breathe more rapidly than adults and so inhale and absorb more pollutants for their body size. Children[xxiv] who are exposed to toxins over longer periods of time, from birth through teen years and beyond, are at increased risk for developing chronic diseases, experiencing lower educational outcomes,[xxv] and becoming trapped in a cycle of poverty.[xxvi]

The air pollution generated by transporting plastics from all over the Southeast region to Macon also carries health implications. Plastics will need to be sorted and decontaminated and unusable materials will need to be hauled away. Some of the products will end up in landfills, which creates an increased risk that toxic pollutants may leach into soil and groundwater—if not directly from the plant itself, then via new and enlarging landfills. This risks contaminating our streams and rivers which would impact fishing and agriculture and thus subject aquatic life, animals, and humans to not only breathing but ingesting harmful contaminants.

Plastics-to-fuel is an energy-intensive, toxic method for processing and burning petrochemicals. It pollutes our environment and consequently harms our health. We urge our elected officials and our leaders at the Georgia Environmental Protection Division and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to consider the consequences of this unproven, wasteful, and harmful technology as they make decisions about the future of the plastic waste and plastic incineration industry in Georgia.

Signed,

- Evan Brockman, MD MPH FAAP, Chair of GCCA

- Amy C Sharma, PhD, Executive Director, Science for Georgia

- Anita L Barkin, Anita L Barkin, DrPH, MSN, Nurse Practitioner, Macon, GA

- Anne Mellinger-Birdsong, MD, MPH, FAAP, Medical Advisor, Mothers & Others For Clean Air

- Brionte McCorkle, Executive Director, Georgia Conservation Voters

- Brooke Lappe, PhD student in Environmental Health Sciences, Atlanta GA

- Christopher Chin, Executive Director of The Center for Oceanic Awareness, Research, and Education (COARE)

- Codi Norred, M. Div., Executive Director, Georgia Interfaith Power and Light

- Dana Barr, PhD, Professor of Environmental Health, Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health

- Dawud Shabaka, Interim Executive Director, The Harambee House / Citizens for Environmental Justice

- Dr. Preeti Jaggi, MD, resident of DeKalb county, GA

- Eric Spears, Ph.D. , Associate Professor of Geography, Macon, GA

- Environment Georgia Research and Policy Center

- Gwendolyn Haile Cattledge, PhD, MSEH, Deputy Associate Director for Science, CDC (retired), Atlanta, GA

- Jan Dell, Chemical Engineer, The Last Beach Cleanup

- Jennifer Barkin, PhD, epidemiologist, Macon, GA

- Jill Neimark, resident of Macon, GA

- Judith Enck, Former EPA Regional Administrator and President of Beyond Plastics

- Kimberly Williams, PhD, Concerned citizen in GA

- Lance Kittel, Executive Director, Inland Ocean Coalition

- Leslie Rubin MD, Founder, Break the Cycle of Health Disparities Inc.

- Linda I. Walden, MD, FAAFP , GCCA, Family Medicine, GCCA, Medical Society Consortium on Climate & Health, Cairo, GA

- Lisa Ramsden, Senior Plastics Campaigner, Greenpeace USA

- Margaret (Peg) Jones, President, Save Our Rivers, Inc.

- Mehul Tejani , MD, internal Medicine at Grady, Atlanta, GA

- Michael Baron, DO, Family Physician in Stone Mountain, GA

- Miriam Gordon, Policy Director, UPSTREAM Solutions

- Preethi Rajan, Resident Physician in Atlanta, GA

- Rachael G. Goodman, Professor of Global Development, resident of Macon, GA

- Rebecca Anne, LCSW, Clinician in Private Practice, Decatur GA

- Ronald Hunter, PhD in Chemistry, resident of Atlanta GA

- Sam Pearse, Lead Campaigner, The Story of Stuff Project

- Sierra Club Georgia Chapter

- Sonali Saindane, Board Chair for the Dekalb Animal Services Advisory

- Tish Naghise, Co-Chair Climate Reality Project Atlanta Chapter

- Tok Oyewole, Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives

- Troy Keller, PhD, Professor of Environmental Science, Columbus, GA

- William Michael Caudle, PhD, Research Associate Professor of Environmental Health, Emory University, resident of Decatur, GA

- Yolanda Whyte, MD, Pediatrician and Environmental health consultant, Atlanta

Sources

[i] S.L. Wong, N. Ngadi, T.A.T. Abdullah, I.M. Inuwa, “Current state and future prospects of plastic waste as source of fuel: A review,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Volume 50, 2015, Pages 1167-1180, (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364032115003330)

[ii] Toloken, Steve. “Study: Chemical Recycling May Need Decades to be Low Cost,” Plastics News. Nov 3, 2021. (https://www.plasticsnews.com/news/chemical-recycling-could-be-low-cost-2050-study-says)

[iii] Patel, D., Moon, D., Tangri, N., Wilson, M. (2020). All Talk and No Recycling: An Investigation of the U.S. “Chemical Recycling” Industry. Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives. www.doi.org/10.46556/WMSM7198 https://www.no-burn.org/wp-content/uploads/All-Talk-and-No-Recycling_July-28.pdf

[iv] Marturello, Mike, “Brightmark Energy moving along on schedule with Ashley Plant,” The Herald Republican, Aug 18, 2019. (https://www.kpcnews.com/heraldrepublican/article_5c91e6e7-540e-51fa-841c-39db1ca8a9bf.html)

[v] Krouse, Peter. “Recycling the once unrecyclable: A technology born in Akron is taking sake in rural Indiana,” Cleveland.Com. Mar 5, 2022. (https://www.cleveland.com/news/2022/03/recycling-the-once-unrecyclable-a-technology-born-in-akron-is-taking-shape-in-rural-indiana.html)

[vi] El Dorado of Chemical Recycling. Zero Waste Europe. 2019. (https://zerowasteeurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/zero_waste_europe_study_chemical_recycling_updated_en.pdf)

[vii] PureCycle Technologies, Inc, CEO Mike Otworth on Q4 2021 Results – Earnings Call Transcript. https://seekingalpha.com/article/4494213-purecycle-technologies-inc-pct-ceo-mike-otworth-on-q4-2021-results-earnings-call-transcript

[viii] Patel, D., Moon, D., Tangri, N., Wilson, M. (2020). All Talk and No Recycling: An Investigation of the U.S. “Chemical Recycling” Industry. Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives. www.doi.org/10.46556/WMSM7198. https://www.no-burn.org/wp-content/uploads/All-Talk-and-No-Recycling_July-28.pdf

[ix] Rollinson, A., Oladejo, J. (2020). Chemical Recycling: Status, Sustainability, and Environmental Impacts. Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives. doi:10.46556/ONLS4535, https://www.no-burn.org/wp-content/uploads/CR-Technical-Assessment_June-2020.pdf

[x] Rollinson, A., Oladejo, J. (2020). Chemical Recycling: Status, Sustainability, and Environmental Impacts. Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives. doi:10.46556/ONLS4535 https://www.no-burn.org/wp-content/uploads/CR-Technical-Assessment_June-2020.pdf

[xi] Patel, D., Moon, D., Tangri, N., Wilson, M. (2020). All Talk and No Recycling: An Investigation of the U.S. “Chemical Recycling” Industry. Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives. www.doi.org/10.46556/WMSM7198

[xii] Brightmark EPA Applications 2021-0382-0138

[xiii] Green businesses and cities at risk: How your waste management plan may be leading you in the wrong direction. GAIA, 2017. https://smartnet.niua.org/content/65072afd-b0d0-4484-a8c9-f4f6a5a4edb0

[xiv] Thomas Bourdrel, Isabella Annesi-Maesano, Barrak Alahmad, Cara N. Maesano, Marie-Abèle Bind. “The impact of outdoor air pollution on COVID-19: a review of evidence from in vitro, animal, and human studies”

European Respiratory Review 2021 30: 200242; DOI: 10.1183/16000617.0242-2020 https://err.ersjournals.com/content/30/159/200242

[xv] https://wwwn.cdc.gov/TSP/ToxFAQs/ToxFAQsLanding.aspx

[xvi] Bourdrel T, Bind MA, Béjot Y, Morel O, Argacha JF. Cardiovascular effects of air pollution. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;110(11):634-642. doi:10.1016/j.acvd.2017.05.003 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5963518/

[xvii] Mustafic H, Jabre P, Caussin C, Murad MH, Escolano S, Tafflet M, Périer MC, Marijon E, Vernerey D, Empana JP, Jouven X. Main air pollutants and myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012 Feb 15;307(7):713-21. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.126. PMID: 22337682. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22337682/

[xviii] Bourdrel T, Bind MA, Béjot Y, Morel O, Argacha JF. Cardiovascular effects of air pollution. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;110(11):634-642. doi:10.1016/j.acvd.2017.05.003 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5963518/

[xix] “Benzene and Cancer Risk” https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-causes/benzene.html

[xx] https://www.epa.gov/ground-level-ozone-pollution/ground-level-ozone-basics#formation

[xxi] “Ozone Media Kit” https://www3.epa.gov/airnow/mediakits/ozone/facts.pdf

[xxii] Gauderman, WJ, Urman, R, et. al. “Association of Improved Air Quality with Long Development in Children.” New England Journal of Medicine. Vol. 372. No. 10. Mar 5, 2015. Pp 905-913. https://www.thoracic.org/members/assemblies/assemblies/peds/resources/NEJMoa1414123.pdf

[xxiii] Rice MB, Rifas-Shiman SL, Litonjua AA, et al. Lifetime Exposure to Ambient Pollution and Lung Function in Children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(8):881-888. doi:10.1164/rccm.201506-1058OC https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4849180/

[xxiv] Landrigan PJ, Rauh VA, Galvez MP. Environmental justice and the health of children. Mt Sinai J Med. 2010;77(2):178-187. doi:10.1002/msj.20173 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6042867/

[xxv] Oersico, Claudia. “How Exposure to pollution affects educations outcomes and inquality. Brookings. Nov 20, 2019. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2019/11/20/how-exposure-to-pollution-affects-educational-outcomes-and-inequality/

[xxvi] Mathiarasan S, Hüls A. Impact of Environmental Injustice on Children’s Health-Interaction between Air Pollution and Socioeconomic Status. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Jan 19;18(2):795. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020795. PMID: 33477762; PMCID: PMC7832299. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33477762/

I appreciate Dr. Sharma and so many others for their work in sharing their data. Locally, the issues of social injustice and military defense (Warner Robins AFB) are also very important in the matter of the proposed site of Brightmark in Macon/Bibb County, Georgia. The site is not healthy for anyone, anywhere.

Peg Jones, President

Save Our Rivers, Inc.