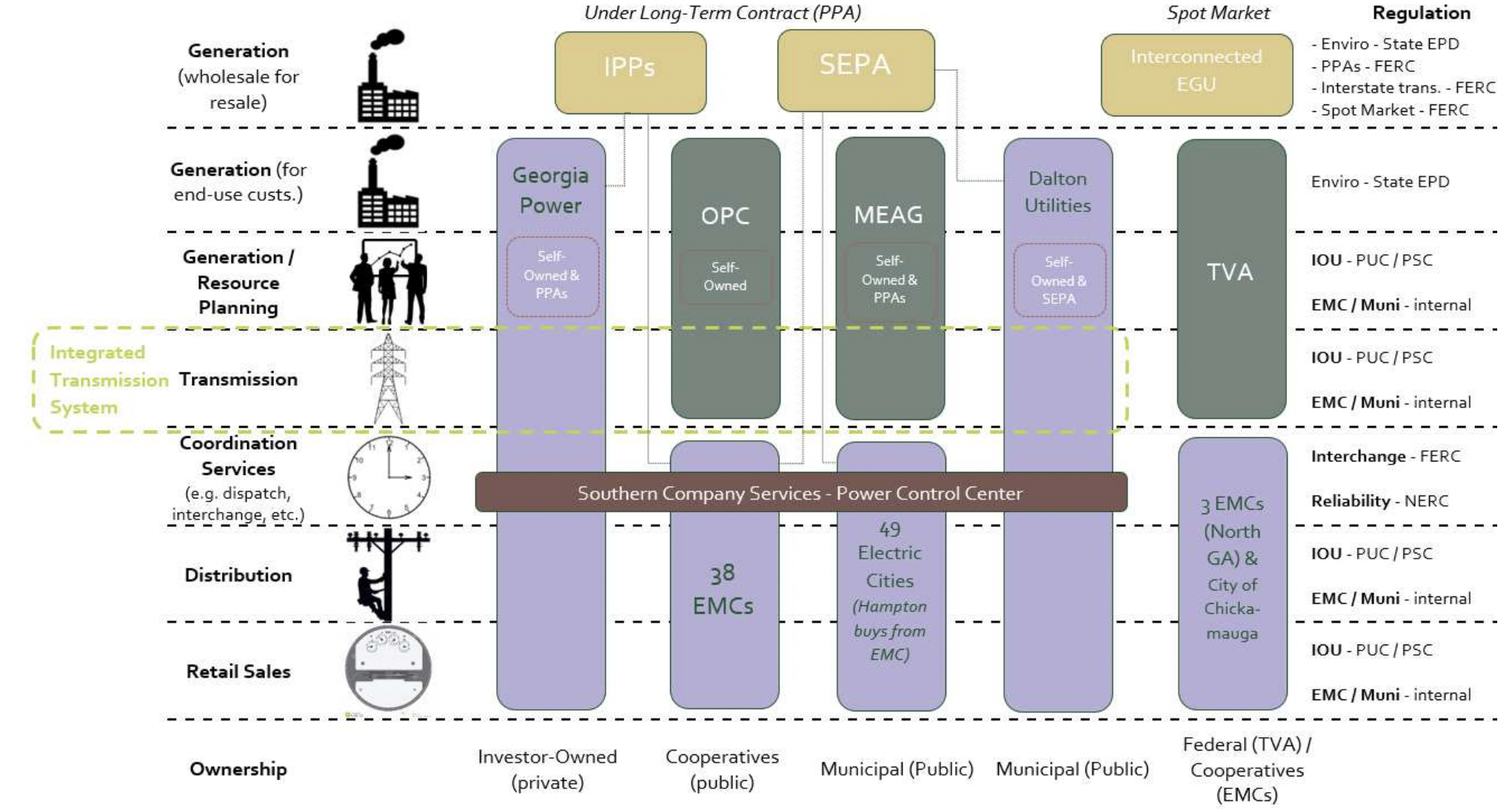

For historical reasons, Georgians get their power from three different types of companies. As the source and cost of our electricity becomes a larger part of the conversation, it is important to understand where we get our power from, who makes the decisions, and what this means for Georgia. Below we provide an overview of the system, include maps of coverage areas, and an overview of some emerging power-grid concerns.

- GA Power, serving mainly the cities, this is the largest operator in the state in terms of customer numbers

- MUNIs, municipal operators who cover smaller cities

- EMCs, Electric Membership Cooperatives, that were formed out of a depression era program to electrify rural areas

The map below shows the territories all three types, GA Power is in green, MUNIs in red, and EMCs in blue.

This map displays the energy provider territories, colored by the type of provider. Zoom in and click on a region of interest to see the name and extent of the provider that normal rate payers must buy their power from.

In the early days of electricity, it was only profitable to build power generation and transmission infrastructure to serve densely populated areas, such as cities. In Georgia, these dense operators became GA Power. Then, smaller cities and municipalities wanted in on the action and voted to form MUNIs that would utilize a mix of taxpayer funds and private rate payers to provide electricity. Finally, the federal government had to intervene in the great depression to get power out to rural customers, as it was never going to be economical for a private company to serve a single rate payer over such a long distance. These rural power providers are the EMCs.

As the state grew, because all these services were private, they began competing for individual rate payers, and mid-century we ended up with situations where a single urban street would have an option for say three different power suppliers, and thus, three sets of power lines. This is a waste of resources and a fire hazard.

In 1973, Georgia passed the Territorial Act, where GA Power, Munis, and EMCs came together and carved up Georgia into territories where within the territory, a single rate payer only has one service option. For example, a resident of Atlanta can only buy their power from GA Power. These territories are outlined in the map above.

This act set rules for how to solve the disputes and unified transmission infrastructure. Since everyone is sending their power over the same lines, these companies participate in centralized power grid coordination.

The graph below, from Southface, shows how the companies are all interconnected to each other.

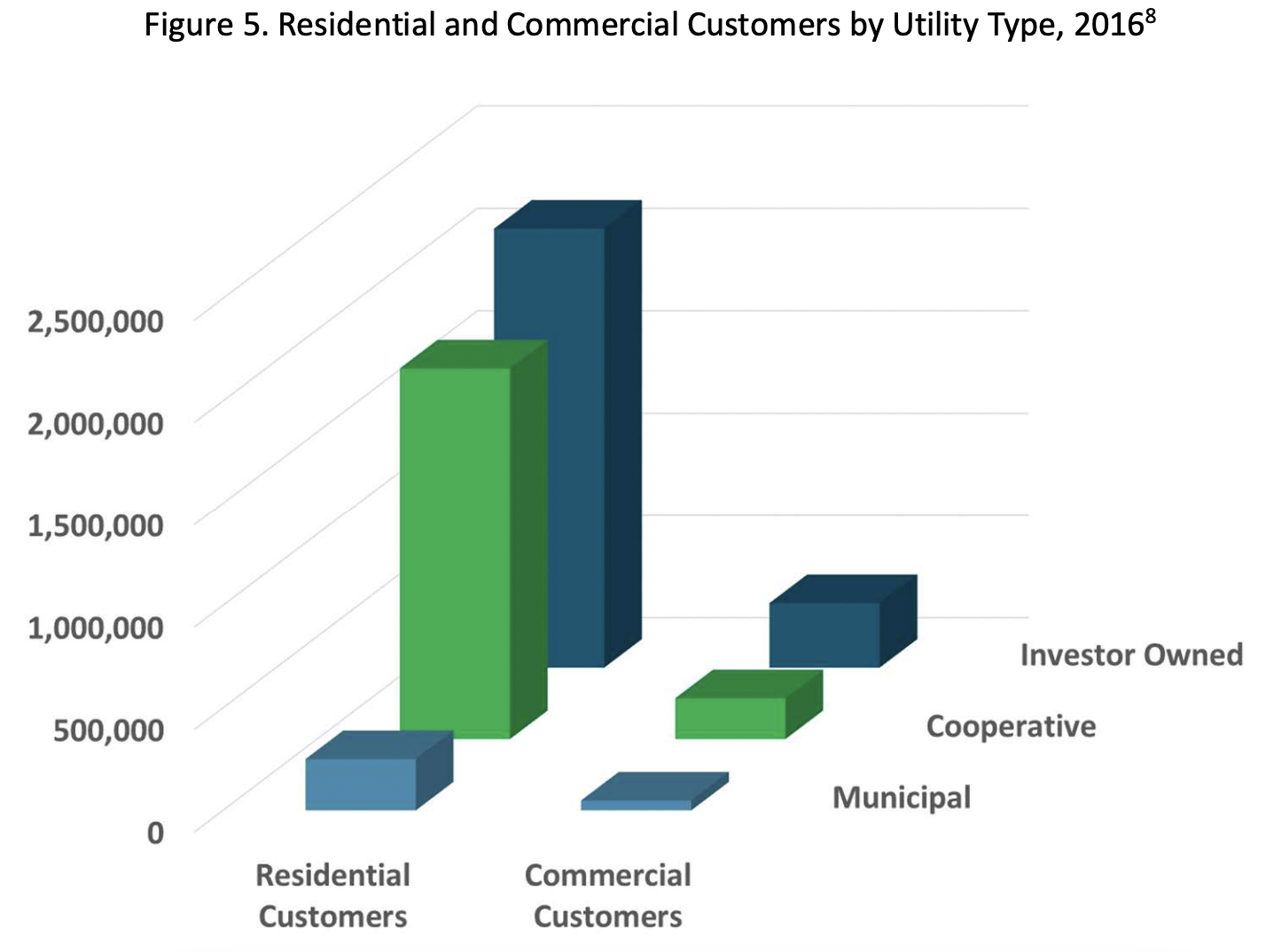

EMCs may cover the largest area of the state, but GA Power has the most coustomers. The below graph, from Southface, shows that a majority of residential customers get their power from GA Power (investor owned), followed second by EMCs (Cooperative), and a small number from MUNIs (Municipal).

What does this mean for consumers?

Citizens of Georgia have no choice about where they buy their power from. To prevent unfair pricing due to lack of choice, the Public Service Commission (PSC) sets rates for GA Power customers (MUNIs and EMCs are supposed to follow suit, but the PSC has no jurisdiction over them). The PSC also plans for how and where GA Power will get their power, including the building of power plants. In theory, the PSC is elected by Georgians, but elections have been on pause for several years due to multiple civil rights lawsuits.

If you live in a MUNI or EMC – there is no such PSC oversight – typically, ratepayers have the power to elect the controlling bodies of these providers.

Are there exceptions?

Yes, if a single facility draws over 900kW (about the size of a modern grocery store), they can choose to contract with any power supplier they choose. They can negotiate their power rate. These rates are often termed “trade secrets” and it is difficult to ascertain how much large facilities pay for the power they consume.

So what's the big deal?

For approximately the past twenty years, power efficiency improvements kept pace with growth. So even while Georgia grew, its overall power demand remained flat. Thus, during PSC planning, they were working on retiring power plants and replacing them with more efficient, cleaner, facilities.

The below map shows electricity generation facilities by type.

This map shows the power sources in the state, colored by the dominant power source.

Unfortunately, in the past few years, industry, including data centers and crypto, mines have been moving into the state at such a high rate, that the projected demand is now much higher than power production. Now, GA Power is asking the PSC to approve building new power plants. New power plants are costly. And their cost is passed onto the rate payer. In the past year, the average electricity bill has risen, on average, $43 a month.

Since large users utilize a negotiated rate that is “hidden” from the public, and since they are creating a majority of the new demand, it is difficult to see if these large demand users are paying their fair share. Or if they are getting a good deal at the cost of individual Georgia households.

In the case of data centers and crypto mines, this is especially unfair, in that both of these facilities do not create jobs for the surrounding communities. Georgians are seeing zero benefits for their increased power bills.

Map of Data Centers and Crypto Mines

Covering the area of Georgia are the colors green, red, and blue, which correspond to the electric provider of a given area. Green represents Georgia Power, red represents Municipal Utility, and blue represents Electric Membership Cooperative.

The black icons represent completed data centers and the orange represent data centers in progress. Gray icons represent crypto mine locations. A number over the symbol represents more than one facility; these will ‘separate out’ as you zoom in on the map.

When you press these icons a pop up appears with basic information: name, address, county, energy source, absolute location (latitude & latitude), and owner. And more detailed information: power usage, total power, total square feet, water source, and water usage in gallons. Much of the detailed information is only estimated due to lack of public information about exact value. For example, the power usage is based on the square feet, and the water usage is based on power usage. See below for the math utilized to estimate these numbers. Blanks in the pop ups indicate a lack of sufficient information to estimate values. The trouble with data center energy figures.

To interact with the map fully, press the “pop-out” icon or click here.

Total Power and Water Usage

| CURRENT DATA CENTERS | PLANNED DATA CENTERS | CRYPTO MINES | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Power Capacity, announced (MW) | 6515 MW (from 68) | 2215 MW (from 9) | 1328 MW | 10058 MW |

| Total Power Capacity, Estimate (MW) | 6610 MW (from 64) | 1781 MW (from 9) | 1100 MW | 9491 MW |

| Total Water Usage, Low Estimate (Million Gal/yr) | 13,219 M Gal / yr (from 64) |

3,562 M Gal / yr | 4582 M Gal / yr | 21,363 M Gal / yr |

| Total Water Usage, High Estimate (Million Gal/yr) | 27,536 M Gal / yr (from 64) |

7,421 M Gal / yr | 2200 M G / yr | 37,157 M G / yr |

Electric Membership Cooperative: Member-owned, not-for-profit utilities that serve approximately 4.4 million of Georgia’s 10 million residents and 73 percent of the state’s land area.

Georgia Power: is the largest subsidiary of Southern Company, one of the nation’s largest generators of electricity

Municipal Utility: are nonprofit government entities that serve at either the local or the state level.

Power Capacity is the maximum operating capability of a data center running at 100%. When a project is announced, it is often stated in MW, the total amount of power it will draw at peak operating capability. On the flip side, the maximum power capacity of a power generation facility is similarly measured in the maximum amount of power it can generate.

Total Power Capacity is the sum of all estimated power capacity of all data centers in Georgia.

Megawatt. A Megawatt is a unit of measurement for electricity that is equal to 1 million Watts. A Watt measures how fast energy transfers from one place to another.

Total Water Usage is the amount of water all of the data centers are using combined, calculated based on their power capacity Since there is very little public information about data centers’ water usage (5), all of these figures are estimates.

27 Billion gallons? Am I reading that right? Yep. To put this into context: an average US citizen uses 132 gallons of water a day. This means that data centers produce enough water every year to sustain 132,368 people for 5 years – larger than the population of Athens, Georgia!

Here at Science for Georgia, we value transparency! At the end of this page, there is a Math Appendix, where you can find the equations used for all of these figures.

We found 97 data centers that are in-use, and an additional 10 more that are in-progress and/or announced.

From those 97 in-use, we were able to find reported power capacity data for 68 centers, and total square footage for 64 centers (not all the same centers). We then used the square footage from the 64 centers to estimate power capacity, and low and high water usage.

For the 10 more in progress, we had announced capacity for 9 of them, and then square footage for 9 of them (note – we had square footage for one data center that we did not have power capacity for). We then used the square footage from the 9 centers to estimate power capacity, and low and high water usage.

- Total Power Capacity, Announced

- This information is usually provided publicly by data centers. See the pop-ups on the map to learn more.

- Power Capacity, Estimated

- Power Capacity can also be estimated from square footage of a center. It ranges from 150W to 300 W per square foot. Here we estimated power capacity by using:

Total Square footage x 150 W / Sq foot

- Power Capacity can also be estimated from square footage of a center. It ranges from 150W to 300 W per square foot. Here we estimated power capacity by using:

- Water Estimate, Low

- Water use estimates vary, but one source suggested that for every 100 MW of capacity, a center uses about 200 M Gallons of water per year.

Using this ratio, the low estimate of water (in million gallons per year) can be found by multiplying total capacity by

- Water use estimates vary, but one source suggested that for every 100 MW of capacity, a center uses about 200 M Gallons of water per year.

- Water Estimate, High

- Another source said that water usage can be estimated using the estimate of 1.8 liters per kilowatt hour. Using this ratio, the math is:

Pwr Usage (MW) x 8760 hours/year x 1000kW/MW x 1.8L/kWh x 1 G/3.785 L=H20 G/yr

- Another source said that water usage can be estimated using the estimate of 1.8 liters per kilowatt hour. Using this ratio, the math is:

- How much water does the population of Athens need?

- 132 Gday365days1 yr5yrs=240900 G5yr ← individual calculation

- 24,681,052,466 Gyr+7,206,461,688Gyr=31,887,514,154 Gyr ← data center calculation

- 31,887,514,154 Gyr / 240900 G5yr=132,368 G5yr

- Plant Vogle Comparison

Provide information about a known Crypto Mine or Data Center

There are a lot of Crypto Mines and Data Centers out there. If you have any additional information to add or update the above map – please use this form to help us out. Thank you!

What about demand pricing?

All power grids are controlled by a ‘central oversight’ that tells power generation facilities when to turn on and turn off to meet demand. When a large power need arises (such as a severe winter storm or a heat wave), these oversight bodies can ask large users to power off their demand. They pay these large users for essentially “giving back” to the power grid in a time of need. Typically, these “buy backs” are a negotiated, flat, rate.

In Texas, in 2021, the buy backs were priced based on “demand” (much like Uber ‘surge’ pricing) and thus, crypto mines and data centers made millions of dollars during the severe winter storm. As a state, we must make sure that “demand pricing” is not a way that large energy users can make money during a time of crisis.

Thank you!

These maps are built, in part, with information from our friends at FindEnergy (energy provider territories) and at FracTracker Alliance (crypto mine locations).